Research

Monumental Inscriptions – Balfron Churchyard

Pat Thomson (BHG Secy.) has been undertaking extensive research into the monumental inscriptions in the graveyard at Balfron Church. A further project of uncovering hidden stones (by permission of Stirling Council) has been undertaken and 65 more inscriptions were added to the booklet. This has resulted not only in a catalogue and photographic record of the gravestones but includes an insight into the social and family history interests which these ‘archives in stone’ hold.

Now in a 47-page booklet CD format, ‘Monumental Inscriptions in Balfron Churchyard’ will be on sale in Balfron Library. A ‘taster’ of this (Pp 1 and 31) can be found in pdf format on the link below.

Dunmore Street Circles

2004 – : Jo Noblett

The Parish of Balfron has a series of sites recognised as Scheduled Ancient Monuments including, of course, the mediaeval Woodend Motte at the junction of Roman Road and Dunmore Street.

Some features on an aerial photograph of this area some years ago caught the eye of current BHG Chairperson, Jo Noblett.

A series of circles between Woodend Motte and St.Anthony’s RC Church on the south side of Dunmore Street showed up quite distinctly on the image and the anomalies were too intriguing to ignore.

The rapid expansion of Balfron and proposals to develop to the south and east of Balfron meant that this site was now in imminent danger and so Balfron Heritage Group took on the task of investigating and protecting this potentially important locale. Lorna Main, Archaeologist for Stirling, was contacted.

At a subsequent talk given by Lorna Main to the Heritage Group, she explained that – interesting as the phenomena were – they would not prevent building in that area. Should housing proposals go ahead, the site might be explored and recorded but it was not a priority area for archaeology.

So it looks as though Tony Robinson and the Time Team crew won’t be descending on Balfron just yet!

If you have any views on this, please contact: info@balfronheritage.org.uk

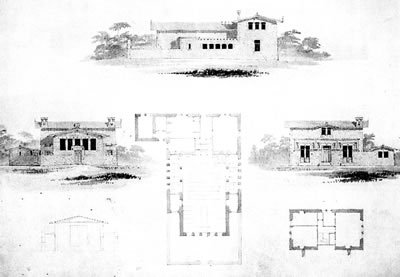

Alexander ‘Greek’ Thomson’s “Unexecuted” Balfron Church and Manse

2003 : Prof. A J Ferguson

Is the church and manse at Holm of Balfron – near Alexander Thomson’s native village – the c1860 design previously thought “unexecuted”?

That is certainly the contention of the present owner of High Honeyholm, Professor Allister Ferguson in his submission to the “Thomson’s Balfron” section of the 2003 Balfron Heritage Group exhibition on “Greek” Thomson. Previous publications and exhibitions had assumed that Alexander Thomson’s only legacies to his native village were the Old South Manse and the Rev. James Thomson gravestone.

Professor Ferguson’s studies of the history of the property had been prompted by Jim Thomson’s 1991 book “The Balfron Heritage” (2nd/updated edition 2003) which made reference to the unexecuted design for a church and manse by Thomson dated 1859 the original drawing for which is in the Mitchell Library. Professor Ferguson was struck at the time by the remarkable similarity between Thomson’s plan and the layout of High Honeyholm. The details were quite different but the layout of the rooms, the joining together of the church and the manse and the way in which the minister could get from the manse straight into the pulpit were remarkably similar.

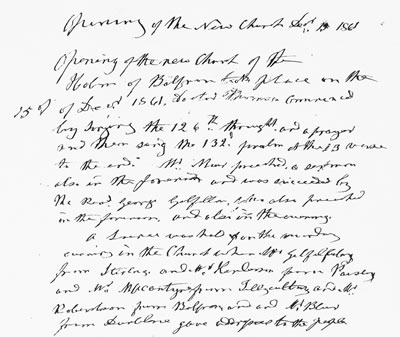

A significant factor was that High Honeyholm was opened in 1861 as mentioned in Guthrie Smith’s “Ecclesiastical History of Strathendrick”.

“In 1861 the Holm congregation had removed from their original church at Edinbelly to a new one erected, not far from their first place of meeting at Honeyholm, on a fine site near the banks of the Endrick, a manse being attached to it.”

This is confirmed in the parish minutes of December 1861 and to Professor Ferguson there seemed to be too much coincidence for Thomson not to have had a hand in the property.

He set about trying to make contact with Ronald McFadzean author of “The Life and Work of Alexander Thomson” the source for the information contained in “The Balfron Heritage”. Ronald McFadzean had obtained a list of all the properties that Thomson had designed from the Rev. John Stark, “who was one of Thomson’s relatives” and that the only design that he had not managed to identify was the church and a manse at the Holm of Balfron.

High Honeyholm is also known as the Holm of Balfron with a stone plaque to prove it and to Professor Ferguson coincidences seemed to be becoming overwhelming.

Ronald McFadzean had “scoured the Balfron area looking for a church and manse along the lines of the drawing in the Mitchell Library” but had drawn a blank. He also said that more recent evidence had shown that Thomson would design in the non-classical style should his clients demand. He had been aware of High Honeyholm but at the time he was writing his book he understood that Thomson would not be likely to design a building with Gothic arches.

McFadzean later visited the property and, according to Professor Ferguson, “his overall feeling was that the quality of the building was consistent with it being by Thomson. He was almost beside himself when he saw the pulpit. There was no doubt in his mind that this was a Thomson pulpit. He left, I think, convinced that the building was indeed Thomson’s lost church and manse at the Holm of Balfron.”

Gavin Stamp – ‘Greek’ Thomson aficionado and then Thomson Society Chairman – had contacted the Fergusons in preparing his book and exhibition for Glasgow 1999 UK City of Architecture and Design. Their reply cited all the evidence above and added – “The Rev. Charles Cooper was the sixth minister at Holm Kirk and was ordained on 23 January 1866 and retired on receiving an appointment at Madras on 3 November 1868. I suspect that there must be some connection between Cooper and `Greek’ Thomson. Thomson’s mother was Elizabeth Cooper who came to Balfron from Aberdeen with her brother Rev. John Cooper who was the first and only Burgher minister in Balfron….”

Although the “Unknown Genius” publication categorises the Honeyholm church as “attribution to Thomson undocumented and uncertain”, that in itself was seen as promotion from being merely unexecuted.

Ronald McFadzean also had an extract from the Alexander Thomson Memorial Minute Book listing Thomson’s churches as “Caledonia Road United Presbyterian Church, St.Vincent Street United Presbyterian Church, Queens Park United Presbyterian Church, Holm of Balfron United Presbyterian Church and Govan Street Free Church”.

Not everyone is totally convinced. Certainly “Unknown Genius” does not endorse Honeyholm as definitely being a Thomson work and, indeed, Balfron’s Community Council still pursues its dream of building, House-For-An-Artlover-like, a Thomson centre in his native village based on the unexecuted plans.

Again, any comments on this research can be sent to info@balfronheritage.org.uk

Vikings on the Endrick Research

1999 – 2002 : Jim Thomson (inspired/initiated by Margaret Callaghan)

This began at a Balfron Heritage Group committee meeting in 1999 when committee member Margaret Callaghan suggested that Vikings might have ‘invaded’ Balfron at one time. After much ‘pooh-pooh-ing’ Jim Thomson began more serious research into the theory.

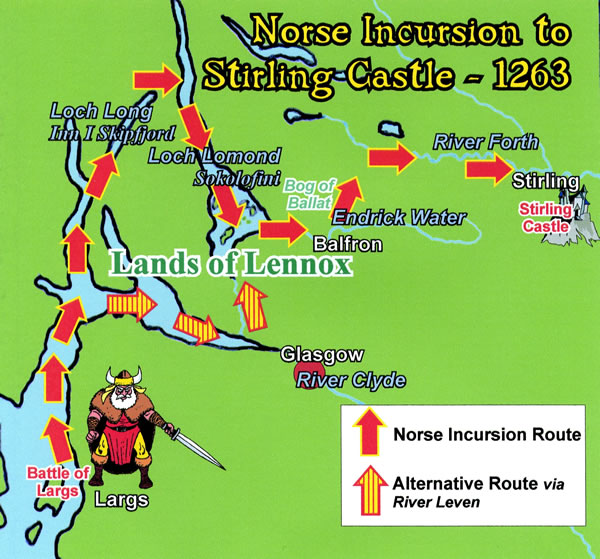

He discovered that, although the hamlet of Balfron itself was fairly insignificant in the early history of the area, it existed near to the main mediaeval ‘highway’ between the River Clyde and the east coast at Stirling when most efficient travel was done by water, clearly illustrated in the forays of Vikings into the Endrick Valley. Perhaps the term ‘Vikings’ is misleading as these raiders bore more allegiance to the Lords of the Isles than to the Norse king. It was, nevertheless, on his orders that they arrived in the area.

We must trace the story back to Somerled who was the first of the ‘sea king’ lords of the isles. While closely linked with Norway, he was an independent ruler of the Hebrides, very much similar to the Lords of Man to the south. His descendants (the sons of Somerled i.e. Mac Somerled [McSorley]) were powerful Lords of the Isles. Because of civil war in Norway and the focus of the Scottish links towards England, the western seaboard was left to the devices of the Somerled dynasty by both the Norwegian and Scottish kings.

By the mid-13th century, however, King Hakon IV of Norway decided to take more direct control of his Scottish dominions and brought his fleet to the Clyde in 1263 to challenge Alexander III the Scottish King who was also turning his attention towards the west.

Although we associate this date principally with the Battle of Largs, Hakon sent a fleet of forty (or, perhaps, even sixty) ships up Inn i Skipfiord (Loch Long) to Sokolofini (Loch Lomond) where, “they burned all the dwellings around the lake and did there great damage”. (Early Sources of Scottish History : Alan Orr Anderson)

This is backed up by “Hakon’s Saga“:-

“Those warriors undaunted

They wasted with war-gales

The islands thick-peopled

On Lomond’s broad loch.

Alan, Dougal’s brother, went almost across Scotland and slew many a man.

He took many hundred neat and did much ravage:

As is here said:

Sturdy swordsmen of the earl

Far in Scotland pushed their forays,

Feeding everywhere the wolf,

Burning dwellings far and wide”

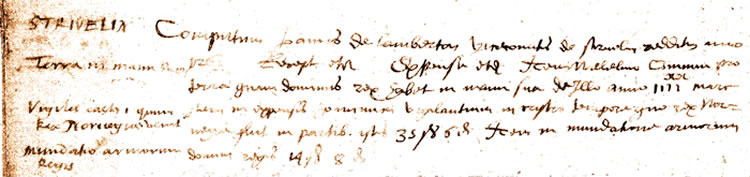

According to the saga, Alan went ‘far across Scotland and slew many men’, perhaps even penetrating as far as Stirling Castle. His invasion of Lennox and beyond would inevitably bring him up the Endrick. Further evidence of this incursion into the heart of Alexander’s Scotland is in the Exchequer Rolls for Stirling (Original extract below courtesy of National Archives of Scotland) which have an entry “…in expensis hominum vigilancium in castro tempore quo rex Noruegie fuit in partibus istis xxxv s. vj d…” (“in expense of lookouts at the time the king of Norway was in the area 35 shillings and sixpence”). (Exchequer Rolls Vol.I, p.24 + The Kingdom of the Isles : R Andrew McDonald)

There is also a macabre twist to this theory of Vikings on the Endrick and that is the Viking practice of “gallcerd” – the tossing of children on spearpoints – which might give a new slant to the legend of the wolves’ attack on the village’s children to give it its name of Balfron, the town of mourning: a name by which it was known only from the early 14th Century onward as we know from the village’s first written reference in a Charter of Inchaffray Abbey in 1303. (Charter of Inchaffray CXIX: [Balfron makes its first documentary appearance on 3rd October 1303 when the jus patronatus and tiends of the parish church of Balfron – known, at that time, as Buthbren – were granted to Inchaffray Abbey by Sir Thomas de Crommenane, knight, and Robert Wishard, bishop of Glasgow, “in compassion for the plunderings, burnings and innumerable afflictions which the abbot and convent of Inchaffray had suffered through war”.])